Jane Allsup walked past the two red plastic gasoline containers every day as she left for work.

“I saw them change color as they aged, and I noticed how they changed shape when the weather was hot and the pressure inside them increased,” she said. “But I didn’t think anything of it at the time.”

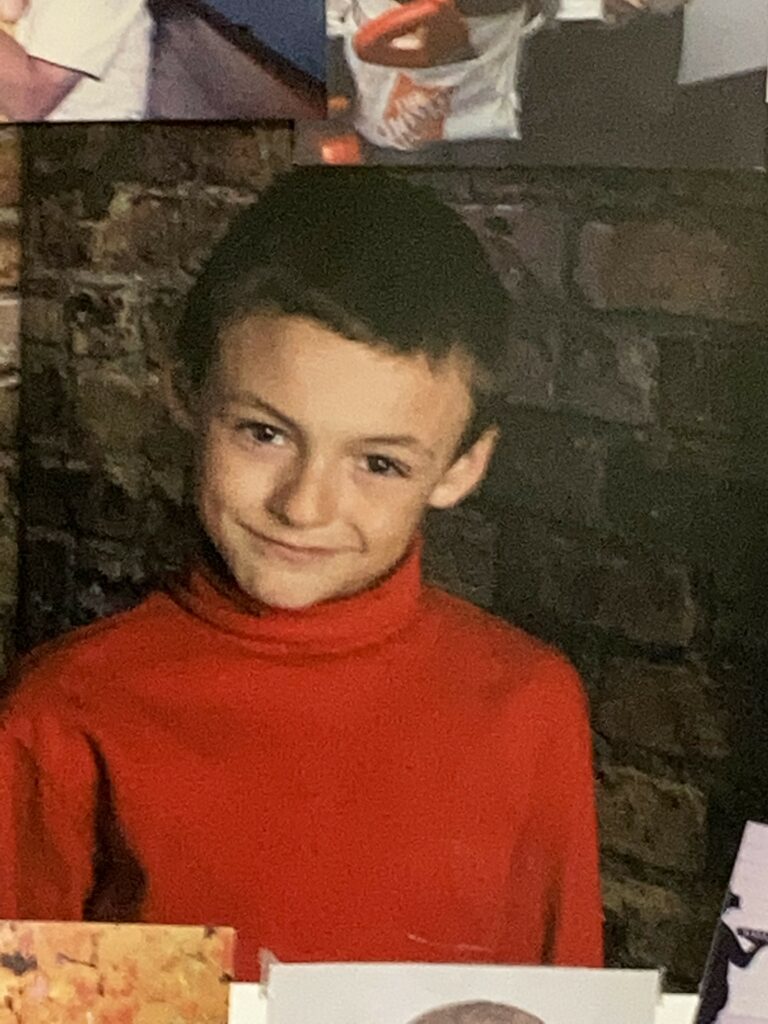

At 6:30 a.m. on a fall-like Saturday morning, Sept. 21, 2013, Allsup began her commute from the family farm in Winterset, Iowa. In the short time between her departure and her husband’s awakening, her son, 10-year-old Christopher Allsup, convinced his brother Chad to go outside. Perhaps recalling family time around the fire pit the night before, Christopher thought it would be fun to start a small fire in the backyard. When newspaper and matches didn’t work, Christopher went into the garage and grabbed one of those gasoline containers that Allsup had walked past so many times. In an all-too-common practice in American backyards and barnyards, Christopher sprinkled the damp, smoldering logs with the accelerant.

Christopher backed away from the fire pit but, unknowingly, stood in a cloud of highly flammable vapors escaping from the old, unsafe container.

“All it took was an ember from the fire to come in contact with the fumes,” Allsup said. “The plastic container exploded like a bomb, showering Christopher with burning gasoline.” The blast was so powerful that it picked up his brother Chad and threw him backward.

A helicopter ambulance flew Christopher, accompanied by Allsup, to the University of Iowa Hospital Burn Treatment Center in Iowa City. But five hours later, Christopher succumbed to burns covering more than 90 percent of his body.

Thousands of Americans are treated each year for burn injuries related to gasoline. Safe practices, such as never using gasoline to start a fire, are key to reducing injuries.

But what of those plastic gasoline containers? Tens of millions of them, many outdated and unsafe, line the shelves of rural and suburban America.

Gasoline handling policy and education have improved since Christopher’s tragedy, thanks to the safety advocacy of Allsup and others who have seen loved ones die or be seriously burned. However, the risk of an explosion remains due to the widespread use of gasoline handling in farm work, yard work, and recreation, and the use of unsafe gasoline cans.

New law

The U.S. Consumer Product Safety Commission (CPSC) now requires all new gas cans and other fuel containers to have flame mitigation devices, known as flame arrestors. Congress required the agency to put rules into place to protect consumers under the Portable Fuel Container Safety Act (PFCSA) of 2020. The gas container rules became law in July 2023.

A flame arrestor could have saved Christopher’s life. A flame arrestor is a mesh screen built into the spout. It allows gasoline to flow out of a portable gas container but will dissipate flashback flames and prevent an explosion.

Many people are not aware of flame arrestors. In a video, recorded at a 100 Women Who Care meeting in Ankeny, Iowa, the speaker asks how many audience members have portable gas containers at home. All hands go up. Do they know if the containers have flame arrestors? Just two hands are raised.

The new law comes after decades of lawsuits, more than 80, were filed against portable gas container manufacturers on behalf of plaintiffs alleging that portable gas cans had exploded and caused serious burns and fatalities. An NBC News report airing three months after Christopher’s death noted that gas can explosions led to at least 11 deaths and 1,200 emergency room visits between 1998 and 2013.

Research underscored the need for flame arrestors. Researchers at Worcester Polytechnic Institute, Worcester, Mass., with funding from ASTM International, an organization that establishes standards for consumer products, studied the conditions under which explosions can occur. They concluded that vapors pose the greatest explosive risk when the gas cans contain two tablespoons or less of gasoline, when the air is cool, and when the container is tilted at a common pouring angle of 42 degrees (WPI Journal, Spring 2021). Additional Worcester research established that flame arrestors are necessary to prevent explosions in plastic gas containers. This video, shot at the Worcester Polytechnic Institute combustion lab, demonstrates a controlled gas container explosion.

Although the new law requiring flame arrestors is a victory for safety, millions of outdated plastic gasoline containers remain in use.

The Legacy of Christopher Allsup Foundation is dedicated to raising awareness about the dangers.

“I don’t want this to happen to another child,” Allsup said.

Why is gasoline vapor so dangerous?

Gasoline vapors are heavier than air and can flow invisibly along the ground before being ignited. A vapor cloud igniting and traveling back to the source is known as a flashback. That’s what happened to Christopher Allsup.

Gasoline has a low flash point and high vapor density. Its flash point is minus-45 degrees (F). Even at that low temperature, there is enough flammable vapor to support combustion when an ignition source (spark, heat, static electricity) is introduced.

One gallon of gasoline is equivalent to 14 sticks of dynamite in explosive force.

Gas can exchanges retire unsafe cans

Since 2014, Allsup has teamed with Safe Kids Greater Des Moines, Blank Children’s Hospital and Metro Waste Authority to host the annual Legacy of Christopher Allsup Gas Can Exchange. Allsup personally greets participants at the event. She tells them about Christopher and the foundation and hands them a brochure about safe gasoline storage and gas container safety. Participants can exchange an old container for a new metal safety container that is fitted with a flame arrestor.

“I feel it’s important that I talk to everyone, so that I know they are getting an education and not just a free gas can,” Allsup said.

The annual exchanges provide about 90 new, safe gasoline containers to the community, along with media coverage and enhanced public awareness.

“You just look at the old cans, and it’s obvious they should have been out of use long ago,” Allsup said. “It would be great if we could branch out to other states.”

Plastic gasoline containers are, “an incident waiting to happen,” said Jerry Minor, a fire chief in rural central Wisconsin. “Yes, they are cheaper, but that’s all they are.

“The metal safety cans not only have vapor protection but have spring-loaded handles, so you must hold them open while pouring, so if the can is dropped, it automatically slams shut,” Minor said. “The cost of a safety can is up there, but a great deal less than a burn center and loss of life.”

Often unaware of the dangers

Allsup secured a pilot project grant from the Central States Center for Agricultural Safety and Health and worked with Purdue University on a project titled, “Gasoline safety on the farm.” The project identified 26 fuel-related explosion/fire cases involving children, adolescents and adults. A review of the cases revealed that incidents primarily occurred while carrying out everyday tasks when safety concerns may be overlooked due to the routine nature of the work.

“The dangers of gasoline are often unknown or underestimated by those handling it,” Allsup said. “People don’t realize they are standing in a highly flammable vapor cloud. This can lead to tragedy, particularly in the agricultural community where onsite fueling is common and where youth are often involved in the handling and use of gasoline.”

The project also produced a video discussing Christopher Allsup, the foundation, and gasoline-handling safety.

Finding strength

Christopher was a loving, vibrant, happy young man, Allsup said. She and her family miss his hugs, smiles and conversations. She also misses the sound of his music. Christopher had begun taking piano lessons.

“Christopher was truly gifted with being able to play beautiful melodies,” Allsup said. “I sure loved to hear them throughout our home.”

Christopher’s brother, Chad, was with him when the container exploded. Chad was 13 at the time, and the two were best friends. They loved driving their go-cart and had big plans of building their houses right next to each other when they grew up.

“Chad battles survivor’s guilt,” Allsup said. “It’s pretty tough. After the incident, we focused on trying to protect him, but it has spilled over to his adult life, too. It’s just tough.

“I never thought something like this would happen to my family. My husband, Scott, and I went to great lengths to always keep the boys safe.”

Allsup said she draws some strength from raising awareness about gasoline container safety.

“If I can get people to think about this and talk to their children about gasoline safety, that keeps me going, knowing that I might save a life.”

General gasoline container safety tips

- Never use gasoline to start a fire or to re-start a fire.

- Never leave fuel containers open, always put the cap back on after use.

- Store gas cans and portable fuel containers in a well-ventilated, cool area out of reach of children. Never store gas cans inside a house, basement or near sources of ignition, such as fuel-burning appliances, open flames, pilot lights, stoves, heaters or electric mowers.

- Always place a gasoline container on the ground to fill up at a gas station.

For more tips, visit the U.S. Consumer Product Safety Commission website.

Additional Resources

- “Sammy the Safety Can and Gasoline Safety” activities booklet, created in partnership with the Central States Center for Agricultural Health and Safety

- Refueling Equipment Guideline: Is your child, or youth employee, able to refuel equipment safely? Refueling is featured in the Agricultural Youth Work Guidelines, which are designed to help adults assign age- and ability-appropriate tasks

The Legacy of Christopher Allsup Foundation, Inc., 501(c)3

- Website

- Facebook Page

- Sammy the Safety Can Activities booklet, created in partnership with CS-CASH

- Sammy the Safety Can and C.W.

The Foundation’s goals

In 2023, The Legacy of Christopher Allsup Foundation, Inc., created a children’s book titled, “Sammy the Safety Can and C.W.,” to discuss the importance of gasoline safety. “This book is one of a kind. We see books about fire safety in the children’s section of the library, but not a book about gasoline safety,” Allsup said. “The Foundation wants children and parents to have access to it.” Another goal, said Allsup, is to partner with organizations and individuals in other states to raise awareness about gasoline safety and possibly bring the Legacy of Christopher Allsup Gas Can Exchange to other communities, as well.

The Legacy of Christopher Allsup Foundation, Inc., is committed to ensuring the safety of children and adults, Allsup said. The Foundation depends on sponsorships, donations and fundraising to continue its work and raise awareness about gasoline safety. Any amount contributed will be greatly appreciated. You can make all your donations to LCAF, 1629 170th St., Winterset, IA 50273.

Previous Post

Previous Post