Valerie Livingston was just walking out of an O’Neill, Neb., store on April 29, 2008, when she and her mother-in-law heard sirens. They thought little about it as they drove to the Livingstons’ 88 Ranch outside Orchard.

“When I heard those sirens, my thought was I hoped I had turned our coffee pot off,” Valerie said. “I never imagined emergency responders were racing to help Craig.”

Reaching their driveway, Valerie saw a neighbor’s vehicle. When she was handed the phone, emergency responders told her to come back to O’Neill and meet them at the hospital.

“I immediately thought something must have happened with my father-in-law, since he was in his 80s at the time,” Valerie said. “In just a few minutes I learned it was Craig.”

Just one day earlier, Craig and Valerie had discussed his plan to vacuum 500 bushels of corn out of a neighbor’s grain bin since the bin auger wasn’t working. The intention was to vacuum out the grain and load it onto a truck to make room for the next year’s harvest.

“Craig talked about how heavy that vac was and how his arms ached from holding it,” Valerie remembers. “We don’t know exactly what happened. If he fell into the bin or the vac plugged.”

The only other person at the bin site was the truck driver, who stepped away for a few minutes to move the truck ahead so they could finish clearing the bin.

“After he moved the truck, all the driver could see inside the bin was Craig’s hands sticking up out of the grain,” Valerie said.

The driver attempted to pull grain away from Craig’s face, putting a handkerchief over his face to help protect him while the driver called for help.

Unfortunately, while emergency responders from nearby Page, Neb., arrived within 10 minutes, the department didn’t have a grain rescue tube and had never trained on using a tube or rescuing someone from grain entrapment. The grain vac wasn’t working, so rescuers had to remove grain one bucket at a time. Craig didn’t survive.

Valerie and her daughters – 10-year-old Cadrien, 18-month-old Carlee, and two-week-old Cassie – found their world completely turned upside down within just a few moments.

“I remember that morning so well. Dad and I sat at this very kitchen table,” now 25-year-old Cadrien said. “Dad always read daily devotions with me before I headed out the door to get on the school bus. I had a blueberry Eggo waffle as he read.”

As Cadrien headed out, her father said, “See you tonight.”

When Cadrien arrived home that afternoon, nothing about the day was normal.

“I thought it was strange that so many vehicles were in our yard,” she said. “We rarely had company. When I walked into the front door, there were neighbors in the kitchen who hardly ever came to visit.”

One of the family’s closest neighbors took Cadrien aside and explained that her father was at the hospital and Cadrien could choose someone at the house to drive her to the hospital to be with her family.

“One of my closest friends took me,” Cadrien said. “I remember praying the whole time we drove, trying to understand what might happen next. At the age of 10, I couldn’t have understood all the things about our lives that would change.”

At the hospital, Valerie’s mother met Cadrien with the sad news of her father’s death.

A love story

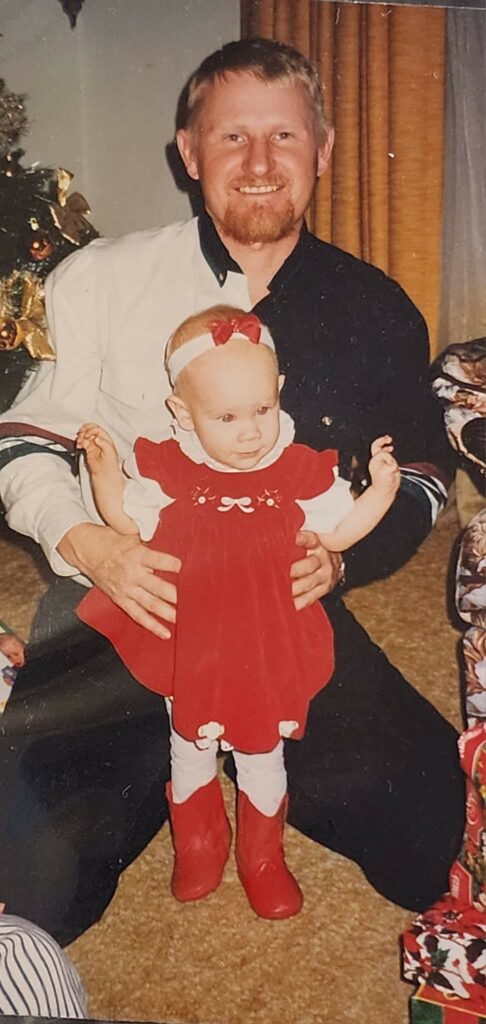

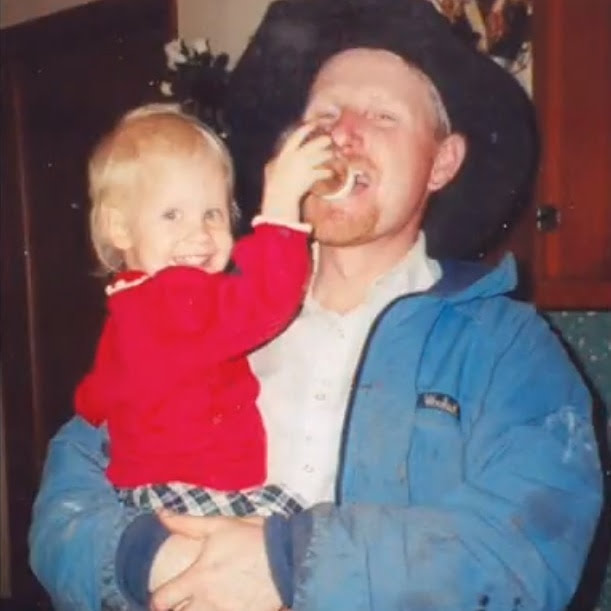

The Livingston family’s story really began in 1984 when Valerie met Craig while the two were in college. Craig’s nickname was “Cowboy,” because he always wore a hat, boots, and western clothing.

“He had a horse, roped at rodeos and rode bulls,” Valerie said. “I needed to borrow a trailer to bring my horse to college. Even though he didn’t know me, he didn’t hesitate to loan his trailer.”

Valerie and Craig’s first date was a rodeo dance, where Valerie says Craig’s outgoing nature, compassion for others, and commitment to living a godly life attracted her attention.

“He really charmed me at that dance,” she said. “We danced well together, and as we talked, we learned we shared the same passion and dream to own a ranch.”

Valerie finished her degree while Craig spent two years in military service. In 1989, after his term in Germany, the two got back together and married that year.

“He wanted to come back to Nebraska and start ranching,” Valerie said. “I grew up in this area and graduated from O’Neill. When we learned of an opportunity here to lease a cow herd, we came to Orchard.”

In 1991 a local landowner knocked on their door, asking if they wanted to buy a ranch.

“We told him we didn’t have the money to do that,” Valerie said. “Then he offered to be our banker and allow us to pay for the ranch over time. That’s how we got started.”

Craig and Valerie discussed designating a name for their ranch, settling on 88 Ranch, in part because the number 8 was a favorite for both.

“We thought about incorporating the Livingston name, but decided if we had daughters and no sons, that wouldn’t work the best,” Valerie said.

The Livingstons put off having a family for eight years until finances improved.

“We had a great eight years, enjoying working and playing together and just having fun,” Valerie said. “When Cadrien was born in 1998, she brought great joy into our lives. We were ready to have more children, but that didn’t happen for another eight years when Carlee was born. Then, surprise, 18 months later, Cassie was born.”

Tough decisions

In the wake of Craig’s death, Valerie had much to work through in terms of what the future looked like for her and her daughters.

“My mom is the bravest person I know,” Cadrien said. “Four days after we lost Dad, Mom and I sat down at the kitchen table. She explained to me that we needed to make some decisions.”

Should Valerie and the girls stay on the ranch? That was the most important decision. Valerie didn’t want to make that choice without talking to her oldest daughter.

“Mom explained that we could stay on the ranch or sell it and go to town and get a job,” Cadrien said. “I remember just wanting our life to go back to normal. As Mom and I talked, I knew I wanted my sisters to have the same opportunities I had to grow up and enjoy ranch life. It was important to me that they had a chance to learn about the rewards of determination, hard work, integrity, and grit. It was also important to me and Mom to keep Dad’s legacy going.”

Remarkably, Valerie and her daughters have not only preserved 88 Ranch. They have expanded their cow herd, developed a network of customers for their bulls, and realized success as beef producers.

“We call ourselves the 88 Ranch Gals,” Valerie said. “We made some significant sacrifices in the first years. But we all agree the struggles were worth it.”

Cadrien not only joined her mother in the battle to preserve the ranch and make it a viable operation. She went on to earn a degree in ag communications at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln, and ultimately pursue a career focused on ag safety.

Carlee and Cassie greatly appreciate the sacrifices their mother and Cadrien made so they could grow up on the ranch.

“My mom and Cadrien are the biggest inspiration to me,” Carlee said. “I could never express enough gratitude to them.”

Cassie agrees about the value of growing up on the 88 Ranch.

“I think Dad would be happy to know we’ve had this opportunity,” Cassie said. “I know he loved the ranch. It’s important and rewarding to me to know we’re able to help Mom and help keep Dad’s legacy going.”

“Faith was important to Craig,” Valerie said. “Both of us knew God is always in control and has a bigger plan for our lives than we can imagine. I knew it was important to trust and live out our faith every day.”

Safety for life

“I want Dad’s life to count for more than just how he died,” Cadrien said. “It’s important to me to share his story every time I can, and do everything possible to make sure no other families have to go through this kind of experience.”

Craig was unaware of the dangers, Cadrien said.

“He grew up on a ranch and he and Mom had never raised grain crops until 2007, when they converted a pasture to cropland to add to their annual income.”

That lack of understanding, she said, coupled with the lack of equipment and training for local emergency responders, “were all part of my father’s tragic death.”

Craig’s story influenced Cadrien’s career path. She is a Midwest regional safety manager for Viterra, an international company that plays a role in supplying essential food and feed products around the globe, handling grains, oilseeds and pulses.

“Every day I travel to some of the 90 Viterra grain elevator sites in this region to provide grain handling safety training and review work practices to ensure they’re done safely,” she said. “It has always amazed me how powerful grain really is, and now that I work with people who are in it every day, my perspective has really broadened.

“In the ag safety industry, we call it, ‘Midwest quicksand.’”

Cadrien and her team approve confined space permits in these elevators, meaning that “crew members’ lives are in our hands when they want to get in and clean out those bins. Sometimes we must make tough decisions on whether a bin should be entered or not.”

While Viterra and other large companies put controls in place to greatly reduce the chances of a tragedy, “many times, farmers and ranchers do not.”

Cadrien encourages her co-workers to share their knowledge with anyone who will listen.

“While you’re sitting at the dump pit with the truck driver, strike up a conversation of safety with them,” she said. “Bring up the dangers of grain and how once grain is past your knees you can’t get out by yourself. And once it’s past your chest, it’s too late. A rescue team will need a rescue tube to get you out. Sharing our knowledge is one of the most important things we can do.”

Grain Safety Facts

Purdue University’s 2022 “Summary of U.S. Agricultural Confined Space-Related Injuries and Fatalities” notes that “there were no fewer than 42 grain related entrapments in 2022, representing a 44.8% increase over 2021.” Agricultural safety officials cannot stress enough the importance of always employing all grain bin safety measures, such as wearing a harness, never entering a grain bin alone, and avoiding bin entry whenever possible.

Efforts to prevent further tragedies include helping producers understand:

- An adult can sink knee-deep in the suction of flowing grain in four seconds and cannot free themselves.

- An adult can be engulfed in grain within 20 seconds.

- Surviving entrapment could mean lifelong disabling injuries.

- When a farmer dies or is severely injured, the family often loses the farm, with negative impacts on both the family and community.

Resources

- Grain Handling Safety Coalition Website

- Stand Up for Grain Safety Week Website

- Preparing Bins for Storage Flyer

- Applying Insecticide to Grain Bins Flyer

- Grain Bin Condition Checklist

- @USagCenter YouTube Channel Grain Bin Safety Video Playlist

- UMASH Farm Safety Check: Stop-Think-Act

More Information

Cadrien Livingston was just 10 years old when her father Craig died in a grain bin. A special branch of the Telling the Story Project focuses on agricultural-related injuries and fatalities that occur in children. Learn more.